KYRENIA – A HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

By Rina Katselli

Kyrenia, the capital town of the district of Kyrenia, lies on the northern part of the island of Cyprus. The district, the smallest of the island, extends form Cape Kormakitis to include a large portion of the Kyrenia Mountains and ends about midway on the island’s northern coast at the area known as ‘Achaean’ shore. This toponym dates to the end of the Trojan War when ma ny settlers arrived there from Achaea in the Peloponnese and established towns in the district. Evidence from archaeological sites excavated in and around the town of Kyrenia bespeak of the area’s settlement since the Neolithic period, 5800-3000 BC. Moreover, many Mycenaean, Geometric and Achaean tombs dating from 1300-500 BC, were also discovered. A fine climate, fertile soil and an abundance of water offered ideal conditions for the town’s early settlement.

ny settlers arrived there from Achaea in the Peloponnese and established towns in the district. Evidence from archaeological sites excavated in and around the town of Kyrenia bespeak of the area’s settlement since the Neolithic period, 5800-3000 BC. Moreover, many Mycenaean, Geometric and Achaean tombs dating from 1300-500 BC, were also discovered. A fine climate, fertile soil and an abundance of water offered ideal conditions for the town’s early settlement.

Kypheas is believed to be the founder of the town of Kyrenia. A military leader, he arrived at the north coast of the island bringing with him many settlers from various towns in Achaea. One such town, located near present-day Aegion in the Peloponnese, was also called Kyrenia.

The earliest reference made to the town of Kyrenia is found, together with that of the other seven citykingdoms of Cyprus, in Egyptian scripts dating from the period of Ramses III, 1125-1100 BC.

From its early days of settlement, Kyrenia’s commerce and maritime trade benefited enormously from its proximity to the Asia Minor coast. Boats set sail from the Aegean islands, travelled along the Asia Minor coast, and then crossed over the short distance to the northern shores of Cyprus to reach the two city kingdoms of Lapithos and Kyrenia. This lively maritime activity (late 4th or early 3rd century BC) is evident in an ancient shipwreck discovered by Andreas Cariolou in 1965, just outside Kyrenia harbour. The vessel’s route along Samos, Kos, Rhodes, the Asia Minor coastline and then Kyrenia, demonstrates the town’s close maritime relations with other city kingdoms in the eastern Mediterranean.

During the succession struggle between Ptolemy and Antigonus that followed Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BC, Kyrenia was subdued under the rule of the kingdom of Lapithos that allied itself with Antigonus. Once the Ptolemies were successful in dominating the whole island, all city kingdoms were abolished. Kyrenia however, because of its maritime trade, continued to prosper. In the second century BC, it is cited as one of six Cypriot towns which were benefactors to the Oracle at Delphi, that is, it received its special representatives who collected contributions and gifts. The town’s prosperity at this time is also evident from its two temples, one dedicated to Apollo and the other to Aphrodite, and from the rich archaeological finds dating from the Hellenistic period excavated within the present-day town limits.

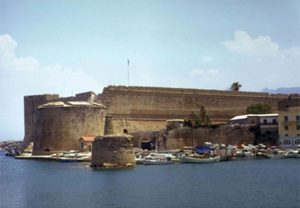

The Romans succeeded the Ptolemies as rulers of Cyprus, and during this time Lapithos became the administrative centre of the district. The numerous tombs excavated and the rich archaeological finds dating from this period indicate however, that Kyrenia continued to be a populous and prosperous town. An inscription found at the base of a limestone statue dating from 13-37 AD, refers to ‘Kyrenians Demos’ that is, the town’s inhabitants. Here, as everywhere else, the Romans left their mark by constructing a castle with a seawall in front of it so that boats and ships could anchor in safety.

Christianity found fertile ground in the area. The first Christian martyrs used the old quarries of Chrysokava, just east of Kyrenia castle, as catacombs and cut-rock cemeteries which are considered among the island’s most important specimens of this period. Later, some of these caves were converted into churches and feature beautiful iconography, the most representative of which is that found at ‘Ayia Mavri.’ From these early days, the town of Kyrenia was an episcopal see. One of its first bishops, Theodotus, was arrested and tortured between 307-324, under the reign of Licinius. Though the persecution of Christians officially ended in 313, when Constantine the Great and his co-emperor, Licinius, issued the Edict of Milan which mandated toleration of Christians in the Roman Empire and freedom of worship, Theodotus martyrdom and persecution only ended in 324 and it is this event that the Church annually commemorates on March 2.

Christianity found fertile ground in the area. The first Christian martyrs used the old quarries of Chrysokava, just east of Kyrenia castle, as catacombs and cut-rock cemeteries which are considered among the island’s most important specimens of this period. Later, some of these caves were converted into churches and feature beautiful iconography, the most representative of which is that found at ‘Ayia Mavri.’ From these early days, the town of Kyrenia was an episcopal see. One of its first bishops, Theodotus, was arrested and tortured between 307-324, under the reign of Licinius. Though the persecution of Christians officially ended in 313, when Constantine the Great and his co-emperor, Licinius, issued the Edict of Milan which mandated toleration of Christians in the Roman Empire and freedom of worship, Theodotus martyrdom and persecution only ended in 324 and it is this event that the Church annually commemorates on March 2.

With the division of the Roman Empire into an eastern and western empire, in 395 Cyprus came under the Byzantine emperors and the Greek Orthodox Church. The Byzantine emperors fortified Kyrenia’s Roman castle. In the 10th century, they constructed in its vicinity a church dedicated to St. George which was used as an army chapel. Then, when in 806, Lambousa was destroyed in the Arab raids, Kyrenia grew in importance because its castle and garrison offered its inhabitants protection and security. So secure Kyrenia castle was believed to be that Isaac Komninos, the island’s last Byzantine governor, sent his family and treasures to Kyrenia castle in 1191 when King Richard the Lion Heart of England went to war with him. Komninos however was defeated and King Richard became the island’s new master.

King Richard’s rule was not welcomed in Cyprus so he sold the island first to the Templars, and then in 1192, to Guy de Lusignan. Under Frankish rule, the villages of the district of Kyrenia became feudal estates and the town became once again the administrative and commercial centre of the area. Its castle was enlarged, a fortification wall and towers were erected around the town and the fortification works extended to the harbour. The Byzantine castles of Saint Hilarion, Voufavento and Kantara were also fortified. Thus fortified, the four castles constituted a defence system that protected the town from land and sea attacks. Kyrenia castle played a pivotal role in the island’s history, the many disputes among the Frankish kings, as well as the conflicts with the Genoese. On numerous occasions, the castle came under siege, but it never capitulated.

King Richard’s rule was not welcomed in Cyprus so he sold the island first to the Templars, and then in 1192, to Guy de Lusignan. Under Frankish rule, the villages of the district of Kyrenia became feudal estates and the town became once again the administrative and commercial centre of the area. Its castle was enlarged, a fortification wall and towers were erected around the town and the fortification works extended to the harbour. The Byzantine castles of Saint Hilarion, Voufavento and Kantara were also fortified. Thus fortified, the four castles constituted a defence system that protected the town from land and sea attacks. Kyrenia castle played a pivotal role in the island’s history, the many disputes among the Frankish kings, as well as the conflicts with the Genoese. On numerous occasions, the castle came under siege, but it never capitulated.

In 1489, Cyprus came under Venetian rule and Kyrenia castle was modified and revamped in order to meet the new military threat posed by the use of gunpowder and large cannons. The castle’s royal quarters and three of its four thin and elegant Frankish towers were demolished and replaced by thickset circular towers that could better withstand cannon fire. These new towers, however, were not put to the test. In 1571, the castle and the town surrendered to the victorious Ottoman army.

Under Ottoman rule, Kyrenia district was at first one of four, then one of six, administrative districts of the island and the town remained its administrative capital. The town’s fortunes declined however as it was transformed into a garrison town. The Christian population was expelled from the fortified city, and no one was allowed to reside within the castle other than the artillerymen and their families. These men terrorized the town’s inhabitants and those of the surrounding villages, Christian and Moslem alike, with their arbitrary looting and crimes. The few local inhabitants who dare stay were merchants and fishermen whose livelihood depended on the sea. They built their homes outside the city wall which through time, neglect and disrepair, turned to ruin. The rest of the inhabitants moved further out to the area known as Pano Kyrenia or the ‘Riatiko’ (so called because it once belonged to a king) or fled further inland and to the mountain villages of Thermia, Karakoumi, Kazafani, Bellapais and Karmi.

The town revived again when local maritime trade with Asia Minor and the Aegean islands was allowed, through bribes and gifts paid to local Turkish officials, to resume. In 1783, the church of Chrysopolitissa was renovated. Then in 1856, following the Hatt-I-Hümayum which introduced social and political reform and greater religious freedom for the various peoples of the Ottoman Empire, the church of Archangel Michael was rebuilt on a rocky mount overlooking the sea. At about this time, many of the Christian inhabitants of the surrounding villages re-established themselves in the town. Local agriculture and maritime trade, particularly the export of carobs to Asia Minor, allowed the people of Kyrenia to have a comfortable living, and some even to educate their children or pursue other cultural activities.

In 1878, following a secret agreement between the British and Ottoman governments, the island was ceded to Great Britain as a military base in the eastern Mediterranean. At first, Great Britain did not undertake major administrative changes, so Kyrenia remained the district’s capital. A road was constructed through the mountain pass to connect the town to the island’s capital, Nicosia, and the harbour was repaired and expanded to accommodate increasing trade with the opposite coast. The town’s municipal affairs were put in order and the municipal council took an active role in cleaning and modernizing the town. In 1893, a hospital was built through private contributions and effort. By the first decade of the twentieth century, Kyrenia was a buzzing little town with a new school building, its own newspaper, social, educational and athletic clubs. It was also a favoured vacation spot for many wealthy Nicosia families. Many homes were converted into pensiones and boarding houses and in 1906, the first hotel, ‘Akteon’ was built by the sea. These first decades of British rule however, also saw increased economic hardship for the population. High taxation, frequent droughts and a world economic depression were precipitating factors for a mass exodus of people from the town and district, first to Egypt and then to the USA.

In 1922, the episcopal see of Kyrenia relocated back to the town after the completion of a new metropolitan building. That same year, the Greco-Turkish war brought to a halt all trade with the opposite coast causing a serious economic depression. To the rescue came a young repatriate from the USA who built the town’s first modern hotels, the ‘Seaview’ in 1922 and the ‘Dome’ in 1932, having a foreign tourist clientele in mind. Kyrenia’s mild climate, picturesque harbour, numerous archaeological sites, panoramic views that combined sea, mountains and vegetation, coupled with modern amenities, soon attracted many travellers and Kyrenia’s economy revived through tourism. After the Second World War, more hotels were built and the town remained a favoured vacation spot for Nicosia residents and foreign travellers alike. To the town’s Greek and Turkish inhabitants were added many from Great Britain who chose Kyrenia as their permanent place of residence.

In 1960, Cyprus gained its independence from Great Britain but Kyrenia’s economic prosperity was halted one more time because of the intercommunal conflict that broke out in 1963-64 between the island’s Greek and Turkish population. While skirmishes in Kyrenia were minimal, Turkish Cypriot irregulars blockaded the Kyrenia-Nicosia road and occupied Saint Hilarion castle. Despite these difficulties, the 1960’s and early 1970’s was a period of lively cultural and economic activity. A new town hall was built and a Folklore Museum established. The ancient shipwreck already alluded to was reassembled and permanently exhibited at the castle with all its amphorae and cargo. The number of new hotels and tourists multiplied and a new road was constructed in the early 1970’s connecting the town to Nicosia from the east. The town’s cultural activities greatly increased. Other than the many traditional cultural and religious fairs and festivals annually celebrated, flower shows, yachting races, concerts and theatre performances were organized. Kyrenia, the smallest of Cypriot towns, was undoubtedly the island’s most precious jewel.

In 1973, the town’s population was estimated at 2,635 Greeks, 1,000 Turks and 254 others (mostly British nationals) who peacefully coexisted and cooperated in their daily affairs. By this time, the town had grown beyond its two historic neighbourhoods of Kato (Lower) Kyrenia and Pano (Upper) Kyrenia. It expanded towards the mountain slopes to form the new neighbourhood of California, and eastward it had just about reached the outskirts of Thermia and Karakoumi. On July 20, 1974, all these abruptly and brutally ended when Turkey invaded the island. The Greek Cypriot inhabitants of Kyrenia abandoned their homes, fleeing for their lives under heavy bombardment by the Turkish air force. Gaining a foothold, the Turkish army at first incarcerated those who stayed behind at the ‘Dome’ hotel. But then, they expelled them all, together with the rest of the district’s Greek Cypriot population, to the Cyprus government controlled area.

In 1973, there were 47 villages in the district of Kyrenia and before the Turkish invasion, the Greek Cypriot population constituted 76.6%, the Turkish Cypriot 13,45% and the Maronite Cypriot 9.95% of the district total population. After the Turkish invasion and ethnic cleansing which ensued against the Greek Cypriot population, only a few hundred Maronites still remain in their villages. Most of the Maronite population was also forced to abandon its homes because of continuous human right violations by the Turkish occupation army. Of a total of 2,500 British permanent residents found in the district of Kyrenia in 1973, just 80 remained there by 1976. Homes, churches, cemeteries, public buildings and schools were systematically looted and destroyed.

While the people of Kyrenia were brutally expelled from their ancestral homes and were forced to endure the pain and suffering of being refugees in their own country, they have not disappeared. Through their collective efforts, their Municipality and Folklore Society they continue their work from Nicosia. Through special voters’ registration and procedures, the people of Kyrenia continue to exercise their separate political and civic rights. The Bishop of Kyrenia continues to oversee to the religious affairs of the community. All traditional holidays, religious and cultural, are celebrated and kept alive by the people of Kyrenia. Through their work, their clubs and societies they vow to never stop fighting for the restoration of their human rights and their eventual return to their homes.